|

|

|

| |

Humanity at its most heroic

‘Art and madness has always been a fascinating topic’ – Howard Hannah previews a new exhibition

IN the old days, artists who had not undergone rigorous fine art training but painted with passion, were regarded as upstarts or not quite the thing. Well there will be plenty of upstarts on show at the Novas Gallery in Camden over the next month at an exhibition called Art Jam.

The gallery in Parkway is exhibiting a wealth of challenging and exciting art produced by people who attend the Creativity Centre off Seven Sisters Road in Islington.

The centre is part of the Camden and Islington Mental Health and Social Care Trust and it offers an environment where people can explore their ability to paint, take photographs, sculpt or make films. Some are art trained but most are not. The only thing they have in common is that all have suffered mental health problems.

Art and madness has always been a fascinating topic. People ask: would a Vincent Van Gogh free from mental turmoil have created those paintings that have endured as masterpieces? But nowadays we don’t generally use the word mad in the context of mental health. Political correctness? Well, it is a derogatory term. Mental illness is seen as fair game as a source of abusive epithets (mad, sick in the head, bonkers etc). And ‘mad’ is in everyday use by us all in ways that are only remotely and metaphorically related to mental health.

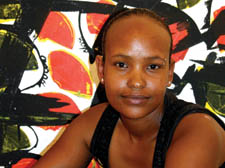

Nimo Younis was brought up in an African war zone. Then as a lone child she struggled to survive in a refugee camp before finally making it to London as a 17-year-old, with no English and no schooling, just an aunt who had escaped earlier. Now a 26-year-old woman, Nimo says she had a lot of mental health problems. But to call her mad would be. . . well, it would be mad.

One of the other artists showing at the Novas describes his process of producing art as “a sanctuary from the madness of the world that I can become lost and alone in”.

Now that kind of madness we’re all familiar with. Nimo, as we have seen, knows something about the madness of the world. “I had a lot of breakdowns,” she says.

She went to the Creativity Centre to start learning photography, but now it’s painting that she loves. “While you are painting you are thinking about things from the past, but even so I’m sometimes surprised with the result.”

Her Abstract with Leaves (pictured) is a tribute to the mother she lost in Somalia. But, she puts another of her works – a blaze of fire and blood circles – to one side. “I don’t think I’ll show that one. That still shocks me. It’s too much.”

Nimo’s horror story is an epic rooted in the horror of grand-scale conflict, part of global political corruption and injustice. But there are more than 20 artists’ works on show. Others’ mental illness may have more mundane but just as intensely painful origins – the cruel claustrophobia of domestic torment, or of chronic emotional neglect. Or it may be the result of chemical dysfunction. Whatever the cause, Art Jam offers a glimpse into the minds of those who have suffered.

But that doesn’t mean unremitting pain and horror. There is also plenty of joy, hope, humour and exuberance in the exhibition. It is humanity at its most heroic and will lift the spirit.

The point of the Creativity Centre is not to produce the great artists of the future, but some of its painters have nevertheless gone on to great careers. Among them was the late Alan Cooper, whose dark East London townscapes and bright cowboy landscapes are now much sought-after works. A room at Art Jam this year pays tribute to his work.

Nimo, in her quiet confident engaging voice, tells how she’s going to do a fine art degree when she finishes a course at the Working Men’s College. But if she’d come out with that as she scratched around to survive in the Ethiopian refugee camp, they’d have said she was crazy.

|

|

|

| |

|

|

|