|

|

|

| |

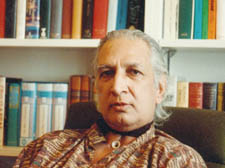

Masud Khan at his home in Palace Court in 1998 |

Masud Khan - inside the mind of a brilliant, flawed analyst

Masud Khan was exceptionally gifted and controversial in equal measure. Fiona Green revisits the life of her friend and mentor as it plays out in an epic biography

False Self: The Life of Masud Khan.

By Linda Hopkins. Karnac Books

OUTRAGEOUS analyst, Muslim, alcoholic, genius, snob, serial adulterer, and anti-Semite: this eloquent and passionate biography of Masud Khan is a wonderful addition to the literature of the world psychoanalytic community; of the man who started as their acolyte, and slowly became their main Nemesis.

Linda Hopkins started her epic journey towards publishing this biography by writing an article, which developed over 13 years into a book.

Before she became a doctor of psychology, and an analyst, Hopkins studied Arabic, and it was this combination of interests that led to her reading Khan’s work, and discovery that he was a Muslim.

She also found out that nothing had previously been written about this extraordinary person, although another book came out later.

The article she started grew and grew, as more and more of his analytic circle talked to her, and the evidence of his influence on his mentors, Donald Winnicott and Anna Freud, became apparent. The enormous network of friends outside this circle gave insight into the vagaries and complexities that made up the character of Khan.

What is evident, as one reads, is that all of his life, Khan suffered depression, and probably a bi-polar illness, exacerbated by alcoholism, which held him in a murderous grip.

Masud Khan was born in Islamabad, in the United Provinces of India – now known as Pakistan. His father was a landowner, whose wealth had come largely as reward from the British; his mother, a young courtesan, and the father’s fourth wife, whom he married at 76 years of age.

Masud was the youngest of his father’s nine sons and his favourite. He witnessed his father’s extreme cruelty and learned most of his sadistic ways from him in childhood.

Masud married twice, both times to ballerinas; the second marriage, to the Russian Svetlana Beriosova, endured for just over a decade, due in part to her alcoholism, and in part to his continual affairs. Hopkins charts these affairs with delicate and discreet care.

During the marriage this pair held salons, where one would find the glitterati of the film world mixing with the world of dance, high society, or fashion. Throughout it all, Khan is helping edit and encourage Winnicott’s writing, while seeing his own patients on a regular basis.

Hopkins describes these times, in 1960s London, sympathetically, where boundaries are crossed as patients become guests, guests sometimes become lovers, while most become witness to both the disintegration of the stellar marriage, and of Beriosova’s descent into alcohol abuse as her career wanes.

When I met Masud in 1986, he was a very sick man, but he accepted me as an analytic supervisee. He was a tall, handsome man, with silver hair and the eyes of an eagle; he glided rather than walked from room to room in his long jellaba in his apartment, at Palace Court in Bayswater. He told me he was a raja, or prince.

Years later he had more operations for throat cancer, losing his rich, velvety voice and only speaking in a gruff whisper, so mostly we communicated by way of notelets or drawings, which I treasure.

I was born in Baluchistan too, 20 years later than Khan, and it helped me understand him.

His fourth book, When Spring Comes, was published in 1988, and the anti-Semitic content – plus his affairs with students – caused him to be thrown out of the Psychoanalytic Society. All his devoted work in helping bolster Winnicott’s reputation was completely overlooked in the desire to punish him.

It was at this time that our roles reversed, and I found myself cooking and caring for him on the occasions we met.

He had resumed drinking his favourite red wine in great quantities, and smoked continuously.

It was this lethal cocktail of drugs that eventually killed him.

Hopkins’s book is compulsory reading on every trainee analysts’ list, because it is a study in the pathology of a man who entered the heart of the analytic world, and who stirred monumental trouble and passionate devotion, in equal measure.

Hopkins shows us the troubled man inside the “false self”: “He lived his life,” Linda says, “as a tragedy on a scale grand enough to match his favourite characters: Shakespeare’s King Lear, and Dostoevsky’s Prince Myshkin.”

As his friend, the psychiatrist Robert Stoller, wrote: “like a kamikaze pilot Khan burnt his house down, with himself inside it.”

• |

|

|

|

| |

|

|

|