|

|

|

| |

Shahrnush Parsipur: a giant of Iranian literature Shahrnush Parsipur: a giant of Iranian literature |

A talent nurtured by years in prison

Shahrnush Parsipur fled Iran in the 1990s to avoid another spell in jail. Now her literary masterpiece is published in

the UK for the first time.

Mohammed Al-Urdun reports

Touba and the Meaning of Night.

By Shahrnush Parsipur. Marion Boyars £9.99.

order this book

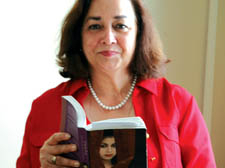

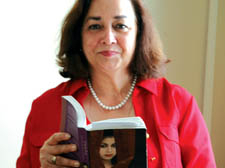

THERE’S something spellbinding about this woman in red. One of Iran’s most revered authors, she’s been translated into several languages and fêted internationally, has spent years in a political prison and now lives in a self-imposed exile.

As only the third woman to have been published in modern Iran, it wouldn’t be gilding her lily to dub her one of the mothers of Persian literature.

It’s been almost 20 years since Shahrnush Parsipur published her bestselling masterpiece Touba and the Meaning of Night, sparking a storm in Iran and wooing European critics. Now, with the first British edition just out, we are at last properly introduced to one of the giants of Iranian literature and to a book that took two decades to arrive.

Neither Islamist nor nationalist, she is expert in Eastern philosophies and describes herself as spiritual and a “woman of the world”.

Dostoyevsky and Dickens are her main literary influences. Of Dickens she decided only to read Great Expectations but, with typical eccentricity, read it 34 times.

Since her first short stories appeared in a literary magazine when she was 16 she has had 12 books published.

In her teens she married “abruptly” and had a son. She went to university and took evening classes, graduating in

her late 20s. It was a “crowded situation”, resolved when they divorced on friendly terms. She moved out with her son and began working on her first novel, The Dog and the Long Winter. In France she wrote her second, Small and Simple Tales of the Spirit of the Tree.

When she returned to Iran in the mid-1970s she protested against the Shah and was imprisoned. A few years after the 1979 Islamic Revolution she was again jailed for political dissent, though she still asserts her innocence.

It was a terrifying time in which thousands were executed and she suffered harsh treatment during four-and-a-half years in prison. She counts herself lucky, however, to have spent formative years with other intellectuals and fellow travellers and to have found the inspiration for Touba and the Meaning of Night.

It is a curate’s egg of a novel, mixing history, mysticism, philosophy and personal tragedy. Set against the backdrop of occupation, war, revolution and social transformation in Iran, it depicts the past century with more pathos and insight than any mere history book.

It is the story of a girl who wants to marry God, who searches for the meaning of life but encounters death, marries a royal but falls on hard times and, in her last moments, has revealed to her the meaning of womanhood.

Written at a crossroads in Iranian history and in Parsipur’s life, the story has special significance for observers of Iran.

Touba’s character is the embodiment of Parsipur’s women: a web of contradictions and complexities, socially repressed yet relentlessly pursuing the meaning of life.

It is a book that stirred strong emotions in Parsipur. When she finished it in jail she she burnt the manuscript, only to rewrite it from memory when she was released. It was an instant hit in Iran and Europe but when in the 1990s she faced another prison spell for her next novel, Women without Men, she chose self-exile in the US. Now she lives hand-to-mouth renting a room from a friend in California.

Parsipur has a complex relationship with America. It has been a safe-haven, she admits, but has never been a home-from-home. In fact she confesses to feeling unsettled – a feeling made worse by the recent war hysteria. She refuses to toss brickbats at Iran. That may appear counter-intuitive considering she has been suffering bouts of serious depression since prison and sees her son only every few years when he can leave Iran to meet her.

She gloomily predicts more wars in the Middle East but pins her hopes on the birth of socialism with a dash of Islam; she despairs of ecological destruction but hopes we find a green solution in our feminine side.

“When I was in prison,” she says, “I was fascinated by some of the women there. They could have been freed, or led different lives, married and been with their families but instead they died for their ideas. I didn’t believe in all their ideas but I believe in their spirit and that their spirit is in the women of Iran.”

With an optimistic laugh she adds: “Iranian women have a tendency to change themselves ... I hope they too will be wearing red in the future.” |

| |

|

|

|

| |

|

|

|

|

Shahrnush Parsipur: a giant of Iranian literature

Shahrnush Parsipur: a giant of Iranian literature