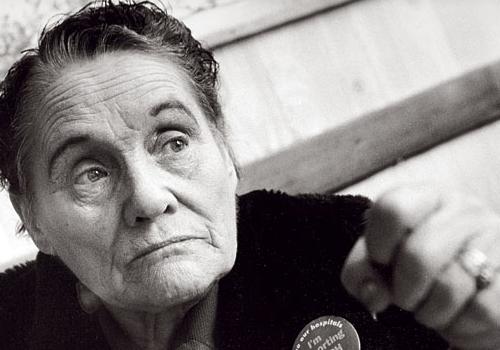

End of an era as Ellen Luby's voice is silenced

Politicians pay tribute to the ‘indomitable fighter’ who spiced up Town Hall meetings with commentary from public gallery

Published: 15 July, 2010

by RICHARD OSLEY and DAN CARRIER

SHE was the last of the hecklers, the feistiest of pensioners who would shout herself hoarse from her favourite place in the public gallery of the Town Hall.

Some mistakenly dismissed her as a figure of fun, her indiscriminate yells were laced with mischief and sometimes delivered at the most inappropriate times.

But Ellen Luby came to represent a dogged, campaigning spirit which even those politicians who faced her angriest broadsides came to admire.

The 86-year-old died in the early hours of yesterday in a cancer hospice, her death immediately described as the end of an era for the little bubble of parochial politics played out at the Town Hall each night.

Her uncompromising and often abrasive style was driven by a belief that the working classes, and pensioners in particular, had been repeatedly let down. Over decades on marches, she protested in defence of voluntary services that faced cuts, in favour of better conditions for hospital staff, improved housing for those most in need and the protection of help for the elderly.

Labour’s Roger Robinson, the longest-serving councillor at the Town Hall, and his wife Maureen, a former mayor, led the tributes yesterday.

He said: “We knew her for more than 45 years and we will miss her very much. Of course, her interruptions at council meetings irritated people but the point to it all was that she cared about people. She was a great campaigner for the elderly.”

As public attendance at Town Hall meetings fell, Ellen Luby did not budge.

Lib Dem councillor Flick Rea said: “I had affection for Ellen – she came from a different time when people cared more about what was happening at the council and would turn up to meetings. She supported lots of people, not always wisely, but did so with a good heart.”

Conservative group leader Councillor Andrew Mennear said: “I am saddened to hear of her death. It really is the end of the era. She was part of the fabric of Camden’s politics.”

She became so much part of the Town Hall culture that if she ever missed a full council meeting her absence was noticed more than a holidaying or sick councillor. Fresh-faced councillors promoted to cabinet positions were told: “’Ere, you got there quick!”

On one occasion, the council warned her that she would be banned from the public gallery if she did not behave – but officials could not stop her piercing barbs.

Born in Clerkenwell in 1923, the daughter of an Irish Catholic father, she attended St Peter’s School in Islington, linked to the Italian church in the area. She left when she was 14 and got a job as a bookbinder. When war broke out, her family home was bombed. They moved along the road, but that too was destroyed in the Blitz. It prompted Ellen and her parents to move to Oxford, the war leaving lasting unhappy memories.

She got a job in a cinema as an usherette and fell for a handsome young projectionist, Tony Taylor. They married and Ellen became pregnant, but their time together was to be tragically short.

Tony was called up towards the end of the war, and in May 1945 was killed by a sniper in Germany, just seven days before guns fell silent. While others celebrated the end of the conflict a week later, Ellen was grieving.

For the rest of her life, the killing of Tony remained very raw. According to relatives, it was a factor that turned her into a lifelong rebel, someone prepared to fight against the establishment.

She moved back to London and lived in Brixton, working in canteens and as a cleaner to make ends meet. In the early 1950s she met her second husband, Douglas Luby. They had a child, Pat, but the marriage did not last.

The couple moved for a short time to Harlow New Town and she loved it, but Douglas, who had known Ellen when theywere children, missed London and they moved back, to Kentish Town. The couple split up shortly afterwards.

In the late 1950s, Ellen was heavily involved in St Pancras council rent strikes. Daughter Pat recalls how her mother and neighbours barricaded themselves inside their flats as the protests against rent hikes and tenancy changes gathered momentum.

Fifty years later, she was among pensioners who barricaded themselves inside Camden Town Neighbourhood Advice Centre, in Greenland Road, to stave off – for a short time at least – a council attempt to evict the service from its office.

Ellen had an encyclopaedic knowledge of film, partly as a result of working as an usher during Hollywood’s golden era.

She had hundreds of DVD versions of classic films, and knew everything about actors, from the films they starred in to minor details about their personal lives.

She also loved music, and while living on the Regents Park estate became a fan of the late 80s dance band Flowered Up.

The band were neighbours and Ellen was respected by the young people there. She would go on their tour bus and could be found at the front, aged 70, with a pint of bitter in one hand, a cigarette in the other, and a band badge on her lapel.

She was also fond of cats; one called Tiddles lived with her for 21 years. But above all, she cared deeply about others in the community around her, and kept a burning sense of injustice alive till the end of her days.

She felt working-class people had been let down by all political parties, and was clear in her outrage at how those who needed society’s help the most were often the ones who were ignored.

Labour councillor Julian Fulbrook said: “At heart, she was an intensely committed individual who assisted many tenants in their struggles.

“Ellen herself had a very tough time of it, particularly when her son unexpectedly died, and in recent years with her own poor health. But she was an indomitable fighter, and many in the borough will know her well.

“It is a sad reflection that my home telephone number will not ring so often, and certainly not at the unexpected hours that Ellen Luby kept.”