|

|

|

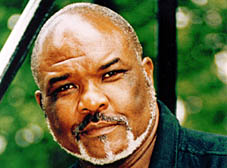

| |

Sir Willard White |

White and Katz are heroes - will Obama be?

ENTERING a concert the other day I noticed two women wearing t-shirts proclaiming Barak Obama a ‘national hero’. What is it, Iwondered, that makes a man a hero?

Inside, St Luke’s Church in Islington reverberated to the sound of Paul Robeson’s songs, reprised by the West Indian bass Sir Willard White. The son of slaves in America, Robeson was a bear-like man who graduated a lawyer and was a ground-breaking athlete before turning to acting and singing in the 1930s. Mastering 20 languages he sang Negro spirituals and folk songs to vast audiences across the world and became an icon of working people in Africa, India, the Soviet Union and China, Europe, Britain and America. His commitment to peace and freedom, for which he was hounded by Washington and stripped of his passport, led him to the Spanish Civil war where he sang on the frontline, the mining pits of Wales, where he’s still remembered, and London, where he helped establish Camden’s Unity Theatre.

Sir Willard, who’s been performing Robeson for years, brought to life songs like Ole Man River, the Song of the Volga Boatmen and Joe Hill, about a Swedish immigrant in America shot for standing up for union rights.

On Friday I popped into a Bloomsbury public meeting celebrating International Women’s Day, and was won over by a slight, self-conscious young Israeli who stood up to tell a story of remarkable courage.

Tamar Katz, a 19 year-old student, couldn’t be more different from Robeson in appearance. Yet she is one of a tiny number of young Israeli refuseniks who say No to military service and have become a symbol of resistance to the Middle East bloodbath.

On a speaking tour, Tamar addressed the audience in stuttering English and blushed as she explained how she was imprisoned for refusing to join the army and suffers daily isolation, abuse and discrimination for continuing to campaign against Israel’s wars.

How, I wondered, could this young woman stand against the state and the fury of an entire society, including her family and friends?

“From the first time I saw the Occupied Territories [of Palestine] I just had to do something,” she said. “My parents, like most Israeli people, are Zionists and expected me to do my service. They supported me when I came back from prison but they are against what I do, which hurts most of all.”

I wondered, as I reflected on these outcast heroes who risk their lives, whether Obama will ever risk his ratings by closing America’s many other secret Guantanamo bases and declaring peace in Iraq, Afghanistan and Palestine?

I saw miners chased down and batoned by police on horseback

TWENTY-five years ago I turned my back on fellow hacks who had been “embedded” with the police during the miners’ strike and reported from the other side.

Nicholas Jones, ex-BBC reporter, described on Radio 4 this week how difficult it had been to report the strike because he and other journalists had been “embedded” with the police.

But I spent several days in the Yorkshire coalfields after a pit called Bentley in Doncaster had become “twinned” with Camden Town Hall.

Anyone with a discerning mind could see the drag of heavy bias in media reports on the strike – hardly any were written by journalists who spent time with the men, and women, who were at the heart of the strike.

One early morning I joined hundreds of miners who drove in convoys to a chosen picket line at a pit near Doncaster. It was as if we were guerillas in a clandestine war: police checkpoints were carefully avoided.

Then we parked in bushes near the pit and walked in file through a wood until the pithead loomed ahead. But at that point all the military-style planning broke down because after the men had emerged in columns from a nearby field, they were soon rounded up by the police.

I, too, was pushed into the crowd of miners. Before us stretched a field. Police on horseback were lining up.

A miner warned what would happen.

The police would “release” the men and then they would be chased across the field, beaten by truncheon-wielding police. I only half-believed him. Could that happen in Britain? Even so, doubts intruded and I wondered if in pursuit of journalistic truth I had gone too far. Then one of the miners asked the police to release me: “He’s not one of us – he’s a reporter,” he pleaded.

I was released by the police, and feeling a coward left my new friends behind. A few minutes later I watched in horror as they were pursued across the field, sometimes beaten to the ground, the men cursing and howling, the police yelling.

I still keep up my friendships with several of those men – some of the finest men I have ever known.

After the collapse of the strike in 1985, life hurtled downhill for many families in the pit “village” I stayed in. Jobs vanished, skilled men ended up as shelf stackers, wives became bread winners, couples split up, drugs appeared on the streets.

But the indescribable sense of community, a tangible throwback to the early years of the Industrial Revolution, though badly beaten remained unbroken. Mrs Thatcher and the government thought they had won – but did they?

In death, I got to know a new Alan

THE saying that men live many lives came to life when I thought about the tragic death of Alan Walter, scourge of those who rule us, friend of the rest of us.

I thought of him simply as a political street fighter. Forever on the go, organising petitions on behalf of council tenants, pleading their case before officialdom. Never still, a 24-hour machine.

The last time I saw him he had just come back from a meeting at the Commons with several Labour MPs with the housing minister Margaret Beckett. He squatted down by the side of my desk, down on the floor to a comfortable position – he suffered interminably from a bad back – and told me all the gossip.

Now, he has vanished. But I had never been to his council flat in Kentish Town until Tuesday, when I met his family, and there in front of a fifth-floor window with a full view in the distance of the Heath, I heard about another Alan – that part of him that had been, until then, part of the “unknowable” Alan.

I never knew he swam 50 lengths a day at the local baths. I never knew he had designed eye-catching posters in his 20s. I never knew he had recently taken up painting, studying at the Working Men’s College in Camden Town.

I was shown his richly coloured paintings – most importantly of all he loved this new-found skill, sketching on holidays, unselfconscious of how bad his sketches might be.

“They’re rubbish, I know,” he told his partner. “Our teacher never puts up my work, it’s too bad, but I love painting.”

Often, only one part of us is turned to the world. The full man never makes it. Perhaps, he shouldn’t. Perhaps, it’s good there are “unknowables” to all of us. But I’m glad I discovered that other part of Alan.

A radical doctor who refused to kowtow

LORD Justice Stephen Sedley used simple English to describe his cousin, Dr Ruth Seifert, at her funeral on Tuesday.

Working as a doctor she wouldn’t kowtow to officialdom, he said, and refused to certify natural causes on the death certificate of those who had died of respiratory disease.

Lord Sedley told mourners at Golders Green crematorium: “She insisted they had been killed by Avoidable Pollution. The local coroner went nuts at the number of inquests that resulted.”

Dr Seifert, a retired consultant psychiatrist at St Barts, died of cancer at 65. Born into a well-known radical Jewish family in Highgate, a recent newspaper profile described it as not religious but strongly culturally Jewish – “We did Passover.”

The sister of Ruth, who lived in Canonbury, Islington, is Sue Siefert, the inspirational head of Montem Junior School in Holloway.

On Maggie and Murdoch

UNLIKE the TV persona of her boss, a certain Mr Gordon Ramsay, the Michelin-starred Angela Hartnett is the most amenable and downright friendly chef I have ever met.

I bumped into her at the official launch of Nonna’s Deli, the side arm of Hartnett’s York and Albany restaurant at the top of Parkway, last night (Wednesday).

“I refuse to read Rupert Murdoch’s papers – I won’t give money to that man,” she told me, adding: “When Margaret Thatcher came to eat at my old restaurant, The Connaught, I wouldn’t get her signature for my mother.

“My mum wouldn’t speak to me for weeks.”

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|